Tanzania 2016

We

are suffering from our long gruelling flight on our journey into

Africa. Matt’s fiancée, Hayley, Mom and sister said goodbye at

Toronto Pearson. As we were jostled through security screening, I

left my laptop in my backpack for inspection. So I was ushered back

through the whole process. This time all went well. I quickly

grabbed my stuff and hustled on. Five minutes passed when I realized

I was about to lose my pants: “My belt,” I mused, "my wallet and

phone!" I returned a third time and everything was sitting in the

open, waiting for anyone to pick them up.

We

are suffering from our long gruelling flight on our journey into

Africa. Matt’s fiancée, Hayley, Mom and sister said goodbye at

Toronto Pearson. As we were jostled through security screening, I

left my laptop in my backpack for inspection. So I was ushered back

through the whole process. This time all went well. I quickly

grabbed my stuff and hustled on. Five minutes passed when I realized

I was about to lose my pants: “My belt,” I mused, "my wallet and

phone!" I returned a third time and everything was sitting in the

open, waiting for anyone to pick them up.

Our Boeing 747, KLM 692 seat configuration

feels like stretchy Levis and making any move greater than a yawn is

sure to bother someone behind, ahead or beside us. We arrive in

Amsterdam after six long hours. While we were going through

Amsterdam Airport Schiphol security, Matt’s shaving cream was

confiscated; it was 50 ml over size. Right now we are somewhere over

Egyptian airspace, cruising at 950 kilometres with the pyramids

10,000 metres below. It has been 28 hours since any distant memory

of sleep. We crash into a bargain hotel, steps away from the airport

in Dar es Salaam.

Ring, ring! The phone, inches from my ear,

jangled at 6:00 a.m. I think we were just starting to doze. It was

Mahona, waiting for us at the hotel lobby, an hour early. His

greeting was sincere and bone crushing, as he lifted both of us off

the ground.

Hanneke organized a visit to the Serengeti to

introduce Matt to Tanzania’s amazing animal heritage. Last night we woke

at 2:00 a.m. when an elephant tried to get into the fenced kitchen

enclosure of our campsite. Our cook finally persuaded him to pack his

trunk and return to grazing by manoeuvring him with the lights of our

safari van. Now we're just finishing our second day in the park. We will

spend tonight in the Ngorongoro Wildlife Lodge, strategically perched on

the rim of a crater 600 metres deep with the world's densest collection

of wildlife sprawled below our window. These are amazing days with the

lions, wildebeest, flamingos, gazelles, giraffes, monkeys, ostriches,

zebras and a newborn hartebeest.

A lazy morning

It’s Sunday morning. A lazy, hazy sun bathes

the Ngoro Crater. From our perch, everything looks so peaceful, so

amazingly perfect. However, below, we remain oblivious to the intrigue

and danger that await the playful young wildebeest or gazelle. While we

head for our toast and cereal, some animals below will become the day’s

breakfast for a predator. So serene, so comforting—but in this fallen

world, we're so far from the reality obscured below.

The Serengeti

plains are vibrant green from the torrential rains. We met up with lions

almost close enough to lick our noses. We had to move our Land Cruiser

out of the way of the rushing herd of elephants or they would have

forced us away without altering their stride—the way they knock over

trees that happen to grow in their path.

We left Mwanza early in the morning to pick up

Mfaume at his school. He has finished school. His marks are good, but he

will have to wait three months for his final results to know where he

can apply next.

The drive to Tabora took about six hours, where we were warmly

greeted by Naomi, Hanneke’s friend and homemaker.

The

project site is ready but today the roads are too muddy to get out

there, so it is a great time to shed our jet lag and chat.

The

project site is ready but today the roads are too muddy to get out

there, so it is a great time to shed our jet lag and chat.

Last night I enjoyed a wonderful rest, but woke

early this morning, riddled with mosquito wounds! Sure hope I don’t

over-stress any effectiveness of my medications. Not sure where the

little critters got in as our net is brand new.

Torrential downpours have transformed mud roads

into slithery ruts, some barely passable. Still, sodden oxcart drivers

and bikers, burdened with charcoal and a myriad of goods, slither along

without pausing.

Yesterday we stood beside a critically ill man

at the government hospital. The ward was sweaty hot and the air felt

thick with the stench of death. His eyes were open but we were unsure

how much he saw. He responded with a weak smile through his parched lips

when I touched his sun-blackened hand—skin barely camouflaging bones.

Hopefully he will improve but his diagnosis is complicated. Hanneke

prayed with him.

A poor family welcomed us into their humble

home. We brought food from the church. The small children dragged out

their few dirty pages of school books—smudged and ragged. These children

remain far behind in their work and the oldest teenage son is unable to

control his bladder. These are hard times.

Hanneke’s nine children fare much better but

not without the usual family challenges. Yesterday Mahona's ears were

painful and he could not hear in class. He relocated to the front, but

he uses binoculars to see the board and then he was too close.

We visited the building project site yesterday

and it looked amazing. A huge tract of land was purchased at a very

reasonable price. When completed, it should soon serve the needs of many

people who otherwise would have to walk up to eight hours for help. Soon

we will begin our serious construction work under the baking sun.

The

bishop and the president

The

bishop and the president

At the office this morning, the bishop of the

Africa Inland Church of Tanzania greeted us. He supports Hanneke and her

work. He's a passionate spiritual leader, yet a very humble man. He was

in Dodoma the previous week at a meeting with the churches serving with

compassion. (Over 200 orphaned and needy kids are fed, taught and cared

for by Hanneke’s church in Tabora. It is a Christian group that cares

for orphans and undernourished children in cooperation with local

churches). Tanzania’s new president, John Magufuli, attended the

meeting. He wanted to meet with this group that was helping the people

in his country. They shook hands and sat together in a circle of leaders

from several organizations. When the meeting was over, his bodyguards

escorted him away from the building. It's a major statement for the

bishop to mention the humility of the president. The bishop asked us to

pray for this man, that being elevated to power as the leader of the

Republic of Tanzania, does not change him and that he will be able to

carry out many of the new visions he has for the people of this

wonderful country. He has already made many bold steps to route out

corruption and waste.

Those African Rains

A heavy, soiled blanket of blue advances across

the sky. Crackling lightning and deep-throated thunder shake the earth.

The rain pounds violently, creating instant rivers and lakes. The lush

mango branches twist cooperatively in the bruising winds. Then as

suddenly as it began, a beautiful, freshly laundered blue sky replaces

the torrents and the sandy red soil drinks her refreshing abundance.

This rainy season has blessed the fertile land. Now the rice, maize,

beans and cassava plants can thrive to feed the nation. Ongoing rains

are a necessary blessing from God.

Driving

Yesterday we drove to meet Ngassa in Mwanza—a

two-day high adventure. Many roads are paved. And that is good but also

dangerous. Paving is poor, rather like making lasagna—a layer of crushed

stone followed by a thin layer of tar, then another layer of gravel,

etc., packed by rubber-tired vehicles before being baked by the sun.

Monstrous trucks pummel the fragile surface. Overloaded donkey carts

meander along the shoulder and part of the road. Bicycles carrying

passengers, chickens and rolled steel vie to use the pavement until a

vehicle honks. A steady stream of pedestrians of all ages is everywhere,

as the traffic roars by at 100 kilometres per hour. Washouts are marked

by tree branches and redundant speed bumps appear like mirages. We

passed a fatal accident, caused when a vehicle passed on a blind curve

and hit a woman walking along the side of the road. We paused to be sure

help was on the way and then proceeded in prayerful silence. Someone’s

mother and wife will not return home tonight carrying cassava roots on

her head. Roundabouts produce their own challenges! You are never sure

that the other road-user has any inkling of obeying the suggestions of

the road. The vehicular choreographed staccato minuet is orchestrated by

the honks and roars of the traffic.

Later we visited several sick folk in the rural

area of Manoleo. Despite their obvious discomfort, they encouraged us.

One 85-year-old gentleman was tilling his field with his three children,

aged 13, 11 and 8. He is a wise, well-educated teacher who never took

time to get married until he was 72. He has the vigour and enthusiasm of

someone half his age. He is so grateful to Hanneke for the help of her

friend, a German doctor, who operated on him and saved his life.

Over 200 orphaned and needy kids are fed, taught

and cared for by the church under Compassion.

Malumba Clinic

Construction

The trench for

the security wall of the new medical centre has been partially dug but

all work has come to a standstill. Our next step is to deepen the

trenches and then drag very large, heavy boulders for the foundation.

Rains and negotiating the cost of labour have crippled any progress—but

then there is always Mañana. After all, THIS IS AFRICA!

The church

service

We pulled up to the simple concrete block

church at 9:45 a.m., just a few minutes late. The sun glared off the

newly installed glass windows. The sound of the choir hammered the air

and caused the glass to vibrate.

Inside, there were over 400 bodies of every age

and size crammed ample hip to ample hip in the wooden pews.

Several churches in the Tabora area have joined

together to celebrate Women’s Day. Each congregation came with at least

one choir. Choir members left their seats and headed to the front,

singing as they swayed. The singers' swinging bodies transferred energy

throughout the congregation. Women ululated, men whistled and many

danced to the beat, joining the choir at the front.

The merciless high-noon sun beating down on the

corrugated steel roof, plus the near- frenzied singing, clapping and hip

swinging raised the temperature to about 40 °C. Bothersome flies were

enjoying the collection of sweaty worshippers. Few paid the flies any

heed, other than occasionally shooing a fly from a youngster’s eye. The

dark, wide-eyed babies held in their mothers' arms and occasionally

nursed, took in everything, especially the pale faces of us visitors.

Heat caused trickles of sweat on the beautiful black skin of the women

crammed in front of us. Flies feasted on all of us with no prejudice.

Sincere prayers punctuated the singing for the

sick, the prisoners and Tanzania's new president. A video located beside

the platform introduced the choirs.

After two and a half hours of intense music, it

was time for the offering. We waltzed to the front to drop our shillings

into wooden boxes. Then it was time for the preaching, followed by other

choirs.

A gentle breeze filled our lungs as we

exited—the singing and worship still coursing through our ears some four

short hours after we had arrived.

The Weaver birds hang upside down while they

weave their intricate nests, singing beautifully all the time.

Today

is a bit less hectic. No trench digging or massive boulder moving. More

relaxing time, even time to catch up on overdue devotions and some reading.

Today

is a bit less hectic. No trench digging or massive boulder moving. More

relaxing time, even time to catch up on overdue devotions and some reading.

Hanneke and Matt bounced off after lunch,

heading upcountry—a four-hour challenge-ridden journey to pick up Jackie

(14), Kiri (13) and Faraja (8), from Rocken Hill Academy. Rocken Hill

inherits its name from its rock-strewn surroundings. It is renowned in

East Africa for its excellent education and life skills. They should

arrive home later tomorrow. Then Hanneke’s home will have five full time

kids plus Matt and me. On the 23rd, Mahona should arrive from Dar on the

bus—a fifteen-hour journey. That just leaves a couple more to show up

closer to Christmas.

The

huge 3,000-litre rain-water tank needed to be cleaned. It is a bit of an

awkward brute with any water inside. Four of us manhandled it until it had

enough tilt to drain. Every drop of water was caught in a bucket or tub.

Although this has been an abundant rainy season so far—raining almost

daily—one can never waste a drop of this life-sustaining liquid. Finally the

stream from the tap became a trickle. Then we wrestled the big hulk to the

ground and onto its side. Mfaume squeezed himself inside through the round

opening in the top, bidding us JAMBO (Welcome inside). For the next thirty

minutes, he sweltered in the heat with the sun beating down on the black

tank, until it was perfectly clean to his exacting standards. When he

re-emerged, he hurried into the house to peel off his clothes and take a

cold shower.

The

huge 3,000-litre rain-water tank needed to be cleaned. It is a bit of an

awkward brute with any water inside. Four of us manhandled it until it had

enough tilt to drain. Every drop of water was caught in a bucket or tub.

Although this has been an abundant rainy season so far—raining almost

daily—one can never waste a drop of this life-sustaining liquid. Finally the

stream from the tap became a trickle. Then we wrestled the big hulk to the

ground and onto its side. Mfaume squeezed himself inside through the round

opening in the top, bidding us JAMBO (Welcome inside). For the next thirty

minutes, he sweltered in the heat with the sun beating down on the black

tank, until it was perfectly clean to his exacting standards. When he

re-emerged, he hurried into the house to peel off his clothes and take a

cold shower.

Mid-afternoon, Mfaume and I walked around his

community. We strolled, often hand-in-hand (so common here), and he

pointed to a house where he had once lived—where he could count the

stars at night through the roof over his bed. We stopped often to just

sit and chat with his friends. He took me into a home of an ex-army

friend. This is where he often comes to watch soccer because they have

cable TV. His friend recently suffered a stroke and we found him flat on

his back on the cool tile floor. Clothed only in a loincloth, he

squirmed closer to shake my hand. His wife and young daughter smiled

weakly as they looked on. He is slowly regaining mobility. Their home is

pleasant and modestly decorated. We were assured of a warm welcome when

we returned. As we meandered home, several young kids wanted to hold my

hands and hear a few words in English. Many would fire off: “Hello, how

are you? I am fine thank you," before you could even respond. Maybe they

would count to ten for me. Swahili is the national language but English

is taught in schools—depending on the quality of the school and the

teacher's commitment. Mfaume's school teaches all classes in English

except for his Swahili class. He's hoping to be approved for higher

education and possibly become a doctor—a common dream—to help his

people. He has a loving, servant attitude.

Naomi, Hanneke’s homemaker, will spend the

night here. She cooked rice, beans, spinach and strips of beef, which we

polished off with sodas.

A small electric fan in Hanneke's guest room

masks the myriad of sounds of the African night: the train with its

extended forlorn horn and clattering rails (the tracks are only half a

kilometre from Hanneke’s home); the rooster with his faulty time-keeping

mechanism; and the dog chorus that can start with the smallest yelp and

carry on for an extended time. Several church choirs frequently practise

late into the night or a wedding celebration might have no end. The

amplifier is the modern curse on the peace of Tabora. Other night sounds

jar you awake and then cause you to toss and turn wondering about the

source. But our fan, that dear little gently purring air-moving gem, is

our good rafiki (friend) during the nights when we have electricity.

Construction progress

As we left Hanneke’s driveway, the crazy

chicken was again pacing in front of her safe, spacious sheltered

hennery that she shared with a dozen fellow bird-brained friends. Their

free-range eggs taste great, with yolks the colour of a setting African

sun. The crazy chicken pecks at the others until they gang up and chase

her through her small escape hatch. Outside she struts triumphantly back

and forth in a 1.5 metre circuit. She glares sideways at her penned

colleagues—clucking about her freedom—her freedom to march in her

self-imposed circuit.

It’s a twenty-minute drive through Tabora, over

countless, redundant speed bumps and then past the Irish-operated

orphanage to the Manoleo clinic. At Manoleo, Dr. Thomas counsels and

treats a variety of health concerns: aids, malnutrition, snake bites,

machete cuts, numbness, blood pressure, typhoid, etc. Today the busy

clinical staff is stitching a young boy. He suffered a blow to the head

from a heavy, sharp hoe. He pleaded for them to stop but that was not an

option. He needed twenty stitches and an examination. Each puncture of

the stitching needle was followed by heart-wrenching screams from the

child. No one uses pain killers here and his essential treatment is more

than the other waiting patients can expect.

The

security wall at the new Malumba health, education and evangelism centre

will enclose 20 x 25 metres. The main building, in the western end of

the enclosure will be 5 x 10 metres with two rooms and a covered

verandah which will serve as a classroom and waiting area. Two bathrooms

will be built at the opposite end of the enclosure. Moringa trees will

be planted inside the walls. Moringa is recognized for its health

benefits: from the dried leaves to the seeds contained in longish bean

pods dangling from their branches.

The

security wall at the new Malumba health, education and evangelism centre

will enclose 20 x 25 metres. The main building, in the western end of

the enclosure will be 5 x 10 metres with two rooms and a covered

verandah which will serve as a classroom and waiting area. Two bathrooms

will be built at the opposite end of the enclosure. Moringa trees will

be planted inside the walls. Moringa is recognized for its health

benefits: from the dried leaves to the seeds contained in longish bean

pods dangling from their branches.

Our workers arrive at the site on bicycles or

on foot—many barefoot, others wearing sandals.

The donkey cart clatters up, weighted down by

huge boulders and sand for the foundation. Four donkeys are yoked

together, two by two. The driver’s wooden cart is old and heavy, even

without the boulders. The driver rides in the cart as well and reminds

the donkeys of his dominance with his all-too-frequent stinging whips.

Water arrives by bicycle from a spring more

than two kilometres away. Four three-gallon yellow plastic containers

are balanced on the bike. Each cost 200 Tanzanian shillings (80 cents)

delivered. The bike has only one speed and dubious brakes.

A

Mediterranean blue sky with pristine white clouds and the sweltering sun

beat down on the plot of land. The trenches have been prepared. So let

the construction begin! Some sparse clouds offer fleeting relief.

A

Mediterranean blue sky with pristine white clouds and the sweltering sun

beat down on the plot of land. The trenches have been prepared. So let

the construction begin! Some sparse clouds offer fleeting relief.

We brought water bottles and a couple of

sandwiches which we store in the shade of a small tree (our onsite

fridge). The local workers drink water from a huge bucket, which looks

milky brown but is wet. They must have some inherited immunity to the

variety of critters that the liquid must harbour.

Fifty-kilogram

bags of concrete, completely dusty and grimy, arrive from Tabora on a

three-wheeled motorcycle-lorry combination. We push the overloaded

bajaji up the final slope. Young men carry the cement bags effortlessly

on their shoulders.

The large boulders are manhandled into the

trench and then smaller ones fitted into the gaps. We mix the concrete

with shovels, turning the sand and concrete mixture over and over before

gradually adding the water. Buckets of mixed concrete are carried to the

fundi (head mason) who organizes everything with a trowel, guided by

tightly stretched strings. Concrete is interspersed with the stones.

Work continues steadily and the finished surface is remarkably smooth.

Nearing the end of the building project, there

will be a need for a system to collect rain water for the clinic.

Although our work day was not long, we arrived

home, tired and very dirty. The familiar clucking of the crazy chicken

welcomed us as she gave us her sideways smirk.

A different day

Well the rains, impassable roads and the

funeral for a nephew of our supervisor have stalled progress on the

site. We chose to adapt to this culture of the people we have grown to

love more and more day by day. Outside, Hanneke’s guard is busy hacking

the lawn with a machete, often hitting stones, Dressed in a blue jacket,

light green pants and bright green boots, he blends gradually into the

lawn. So with no progress to report, I’ll just recount a few thoughts of

urban Tabora.

The electricity has been off for over thirty

hours. The temperature in our room is escalating in sync with the

humidity. My feet have dragged enough sand into my bed to give me dermal

abrasion. After crawling into my bunk, I quickly realize that I am far

from being alone. Mosquitoes hover like buzzards. These tiny demons with

their potentially lethal cargo are so small that you don’t feel them

land until it's too late. Sweltering and swatting in total darkness

accomplishes nothing. I discovered near morning, that the mosquito net

was snagged on the ladder and draped open as a warm welcome to my

enemies.

The neighbours have two hound dogs. Although I

have yet to see a moon here, they must sense one. One begins to yowl and

then is joined by his colleague—that mournful eerie wailing of

desertion. Many other, far less melodious canine creatures join the

chorus with superior volume. This continues for five minutes, then after

a brief intermission, begins again with renewed vigour.

Tabora’s downtown market is a jumble of shops

and stalls. The stench of dagaa penetrates every nose first. Dagaa is a

small sardine-like fish from Lake Victoria where they are sun dried and

shipped throughout Tanzania. They are a very good source of protein and

omega-3. I wonder how there can be any space for water in the lake with

the quantities of dagaa that exist. Huge stacks dominate most food

stalls. When they are dried and transported, their tiny scales become

airborne dust that coats the lining of the nose.

Then there are the meat mongers. Carcasses hang

in their open shops, festering with flies. Hunks are hacked off and

plopped onto a balance-scale and it quickly becomes impossible to

identify the animal sacrificed. Chickens squawk to avoid being chosen

for some mama’s family dinner. Non-continuous tarps droop between the

stalls to keep out some sun and some rain. In pleasant contrast, fruits

and vegetables offer a beautiful tapestry of colour and fragrances.

Competing merchants share tables or stalls. Sputtering generators mix

their fumes into the overall ambiance. Shoppers jostle through the maze

of maize and rice. Merchants grab your arm to encourage you to visit

their shop. Clothing shops are interspersed throughout the market. They

are usually deep and narrow with little light. Shoes and clothing

hanging from the ceiling make them feel like a bat cave. We squeeze, all

eight of us, into an area snug for one person half our size. Ten shops

later and we have two fine dresses and two handsome shirts for the kids’

Christmas. Wriggling our retreat through bikes, carts, rows of parked

pikipikis (motorcycles), bike taxis and boys carrying loaded soda cases,

we breathe fresh air again, still clutching our purchases. We arrive

home as exhausted as we would have been after a heavy day’s labour—just

three hours later.

Nostalgia

Today,

it started raining with the rooster’s crowing. Now it is noon and the

heavy clouds are beginning to meander off. African rains pound in

torrents, then lessen to a heavy downpour—so wonderful for the crops.

Usually they last about twenty minutes, but today was an exception. We

celebrate a rain day with Hanneke and the kids—doing laundry, emails,

shopping and helping the kids prepare school supplies for boarding

school.

Today,

it started raining with the rooster’s crowing. Now it is noon and the

heavy clouds are beginning to meander off. African rains pound in

torrents, then lessen to a heavy downpour—so wonderful for the crops.

Usually they last about twenty minutes, but today was an exception. We

celebrate a rain day with Hanneke and the kids—doing laundry, emails,

shopping and helping the kids prepare school supplies for boarding

school.

Inside one of Tabora’s three prison compounds,

the army has opened a store—operated like a mini warehouse. They import

an array of merchandise: fruit juices from Egypt; canned goods from

Europe; cereals from Dar es Salaam; small and large appliances from

China; mattresses from Kenya; furniture from China; soap; snacks and

electronics from Korea and Vietnam. When shipments sell out though, you

can never be sure of a re-supply. There are several security checks on

every purchase. There are no credit cards and likely no change in the

till, so shoppers have to pick out some item equivalent to their change.

Many items are not available anywhere else in Tabora and prices are

lower than elsewhere so the store is popular even with the street

vendors.

At

the Malumba site, we await the donkey cart with more big boulders to

complete the foundation for the wall. We purchased more concrete which

needs to be stored in a secure location or it might just get borrowed.

The bags were moved on bicycles.

At

the Malumba site, we await the donkey cart with more big boulders to

complete the foundation for the wall. We purchased more concrete which

needs to be stored in a secure location or it might just get borrowed.

The bags were moved on bicycles.

On our return from the site we passed a young

mother walking with her infant daughter, struggling through the noon-day

heat on her way to the Manoleo clinic. Her child, strapped to her back,

had diarrhea and a fever and was already showing signs of

dehydration—all familiar symptoms of malaria. The unfortunate down side

of this great rainy season means increased mosquitoes and, consequently,

malaria. The young mother had been walking for over one hour and faced

another two hours to the dispensary. Hanneke offered her a ride in our

van. The tiny mama was not familiar with riding in such a vehicle and

with the first lurch in the road, she was tossed into the air and came

to rest next to me, with her hand clutching my leg. She was mortified

when she looked—but when I laughed, she laughed too and the little baby

showed her two bottom teeth in a giggle. We dropped them off at the

clinic to get her sweet daughter the much- needed help.

Back home, two

bicycles needed repair. Neither had brakes and both had flat tires. Matt

and I wrestled them the two kilometres into town. Squatting along the

road with a metal tool box, a fundi (bike repair expert) offered his

service. He knew how to fix bikes with a minimum overhead. After over an

hour of work and chatting, he had replaced the brake cables, put three

patches on one tire and supplied new brake pads. He adjusted and oiled

the chains and finished by wiping every inch of the bike frames clean.

The cost was $3. He wished us karibu

as we rode our remanufactured bikes onto the sandy road.

We heard sounds at the Tabora railway station

so we rode by to check out the local commotion. It was just another day

at the station. One hundred or so people milled around and a freight

engine shunted box cars, belching sooty black smoke. One woman purchased

a ticket, which took about ten minutes. We searched for a passenger

schedule but to no avail. We would like to take the train when we leave

Tabora, but lack of reliability would likely mean missing our flight.

Inside the waiting area, thunder cracked out of the blackening sky and

we jumped as the noise shook the metal roof. Many standing outside raced

for cover as rain cascaded. Numerous gaps in the roof meant you had to

choose your spot wisely. As we waited out the storm, the station

manager, in a spotless white shirt and tie, came to chat. He had been in

Toronto and loved the underground train system there. He was proud of

the improvements in the Tanzanian rail system, despite the need for a

massive investment in infrastructure. Tabora station is tired and shows

her age and years of neglect. There are several new Chinese-made

passenger carriages. The rusted ribbon of steel stretches across

Tanzania, twisting like a cobra, linking original urban areas together,

so journey times are excessive, Nevertheless, the journey is without

equal.

Jackie's prayer

Jackie

is a very sensitive and attractive young woman. Jackie is one of

Hanneke’s ten children. Hanneke prefers to be called Bibi

(grandmother) although some kids insist on calling her Mom. Jackie has

experienced more than her share of difficulties in her fifteen years.

She is aware that she was abandoned by her birth family and that a

possible adoptive family has just withdrawn their application. She has

tearful moments but displays amazing resilience. She has become close

enough to Matt and me to tease us, calling us bad gringos. This morning

she asked if I ever went to the gym. I said maybe a long time ago.

“Well,” she said, “you don’t look like a gym person to me. You have too

much meat!”

Jackie

is a very sensitive and attractive young woman. Jackie is one of

Hanneke’s ten children. Hanneke prefers to be called Bibi

(grandmother) although some kids insist on calling her Mom. Jackie has

experienced more than her share of difficulties in her fifteen years.

She is aware that she was abandoned by her birth family and that a

possible adoptive family has just withdrawn their application. She has

tearful moments but displays amazing resilience. She has become close

enough to Matt and me to tease us, calling us bad gringos. This morning

she asked if I ever went to the gym. I said maybe a long time ago.

“Well,” she said, “you don’t look like a gym person to me. You have too

much meat!”

Today at the Manoleo clinic, while we worked on

the entrance door, the silhouette of a gaunt young boy appeared in the

open doorway. He had walked five miles carrying his ten-year-old son,

Maige, on his back. (Maige and his family live in Malumba, the village

where we have started the new medical outreach building). His brother,

slight for his years, was feverish and had a large boil on his foot. The

boy needed hospitalization. He was malnourished and likely had malaria.

The government medic gave him an aspirin, lanced his foot and wrapped it

in a few layers of gauze but he had no malaria medication in stock. The

boy lay on the cool clinic floor in agony, his sunken chest heaving with

every breath and blood oozing through his bandage. The white of his

beautiful eyes were taking on a greyish hue. Hanneke provided medication

for his malaria and an antibiotic against infection. She gave the father

careful instructions for their use.

While his father

was with Hanneke, Jackie tried to comfort the boy in so much pain. She

asked if she could pray for him. Her gentle Swahili voice prayed for her

new friend curled up at her knees. Her gentle crescendos betrayed her

emotions.

The stale smell of his feverish body became almost pleasant.

We drove the five miles to their home. The boy

sprawled across the seat. His father carried him up the path to their

home. Their humble dwelling was a red mud brick construction with an

aging thatched roof, so many miles from the closest help. As they faded

in the distance, obscured now by a mango tree, any confidence that the

young boy would recover was based solely on overhearing Jackie’s appeal

to her Father for little Maige.

David Livingstone

The

historic tembe (home) of David Livingstone stands on a gentle rise of ground

just ten kilometres outside Tabora city. Tabora region sprawls below with an

occasional new steel roof shimmering in the sub-Saharan sun. Our trip is a

pleasant twenty-minute pikipiki (motorcycle) ride. Livingstone, born in

Scotland in 1813 and buried in Zambia in1873, was a committed missionary,

explorer and anti-slave advocate.

The

historic tembe (home) of David Livingstone stands on a gentle rise of ground

just ten kilometres outside Tabora city. Tabora region sprawls below with an

occasional new steel roof shimmering in the sub-Saharan sun. Our trip is a

pleasant twenty-minute pikipiki (motorcycle) ride. Livingstone, born in

Scotland in 1813 and buried in Zambia in1873, was a committed missionary,

explorer and anti-slave advocate.

Arriving

at the Livingstone tembe, Mahona, Matt and I were welcomed by a

Tanzanian tourist guide. He spoke excellent English, sharing his

knowledge of Livingstone and his tembe with enthusiasm.

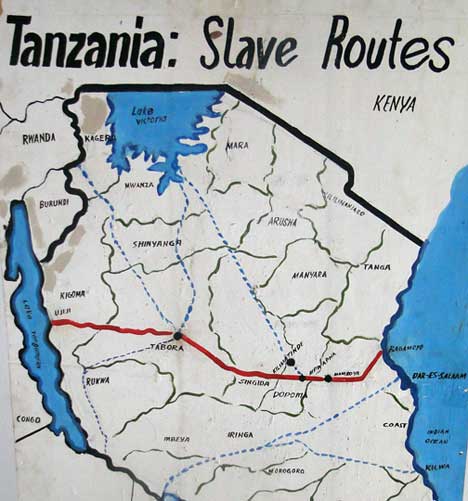

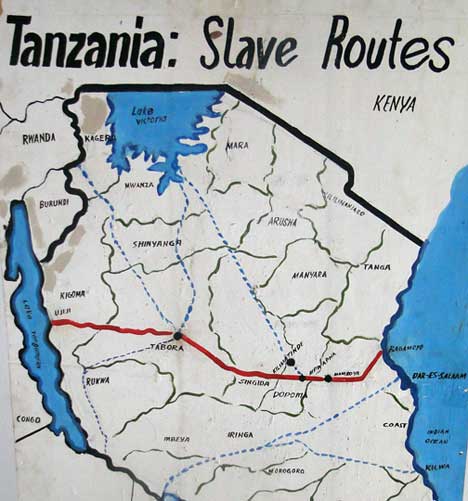

This

rambling mud brick structure was constructed by an Arab slave trader.

The owner offered accommodation to Livingstone, hoping he would help

secure a better route for his diabolic business. Livingstone refused.

The home served as a holding tank for slaves taken from Uganda and

western Tanzania. Tabora is located on the critical east-west route.

Today huge mango trees populate the area, often a result of seeds

dropped by slaves on their endless march. The facility can hold a

maximum of two hundred slaves. The slaves were then driven to the Indian

Ocean, over 900 kilometres away (two or three months) and barged to

Zanzibar Island, to be displayed in slave markets like livestock.

Livingstone

attempted to persuade his Arab host to give up his slave trade but he

refused, abandoning his tembe to Livingstone instead. Livingstone didn't

live in this home for long. He remains a world-celebrated medic, devout

missionary and an explorer who charted large areas of east Africa, while

seeking the source of the Nile River.

Livingstone

attempted to persuade his Arab host to give up his slave trade but he

refused, abandoning his tembe to Livingstone instead. Livingstone didn't

live in this home for long. He remains a world-celebrated medic, devout

missionary and an explorer who charted large areas of east Africa, while

seeking the source of the Nile River.

Display cases

contain articles, including a copy of the New York Herald—the newspaper

that funded Lord Stanley to travel to Tanzania to discover if

Livingstone were still alive. Rumours of his death had spread. Stanley

is credited with his famous quote on meeting Livingstone: “Dr.

Livingstone, I presume!” Livingstone died in Zambia shortly thereafter

of malaria, typhoid and internal bleeding.

Rusted shackles and yokes, clanking around our

necks, helped us understand firsthand the oppressiveness the slaves were

subjected to. Slaves were chained in pairs at all times. Any slave who

became ill or feigned illness would be hacked down in front of the

others as a grim example. Christian missionaries who began the early

Christian church in Tanzania often purchased the slaves in the Zanzibar

markets to offer them freedom.

The final holding room close to the market

above, with only air slots high in the walls, would have been unbearably

crowded and sweltering. The final test of stamina. A well-furnished

kitchen with a very competent resident cook ensured that the slaves were

well fed so that they would bring in extremely high bids.

After experiencing the oppressive chains and

heavy yokes around our necks, we rode back to town on the back of our

pikipikis, owned by totally free black Tanzanians. The fresh air blew in

our faces as we relived these dark years of African history, while we

thanked God for men like David Livingstone who gave their lives that

others might live free spiritually and physically.

Mama

Tatu’s Chapati

Mama

Tatu’s Chapati

Today we feasted on the most delicious chapati

imaginable. The ambiance did enhance the taste. A small, mud brick hut

is situated across the road from the Manoleo clinic. Inside Mama Tatu’s

one-room restaurant, a charcoal fire glows in her cooking stove. Mama

and her two daughters are delighted to have customers from the

other-side-of-beyond location. They quickly begin mixing corn flour with

water,—first with a wooden spoon, then by hand, forming the dough into

smooth balls. A round stick is used to roll the ball flat. Mama Tatu

lightly oils her flat frying pan and places the dough on top. Soon big

bubbles form and she flips it over a couple of times, applies a little

oil on the outer edge and rubs inward with a spoon. She serves her

flatbread with salt and hot, sugary tea. Simple maybe, but Mama Tatu’s

chapati definitely is amazing. We teeter on two benches propped against

the wall as we appreciate our meal. The charcoal smoke tinges the room.

The interior is only illuminated by the open door and small window. We

bend low to exit Mama Tatu’s with her invitation to return. Our bill, a

meal for four with beverages, comes to approximately one dollar and no

tip is expected.

The Orphanage

There are sixteen orphans under

ten years of age at the newly opened Catholic orphanage.

Plans are in order to increase the number of children in

the orphanage as soon as the new on-site school facility

is completed. Three sisters, all from Ethiopia, look

after the kids with love and understanding. Pictures of

Jesus hang on the walls, a reminder that Jesus is the

source of their love for these young lives.

We took balloons, Canadian

flags, bracelets, pens and a soccer ball from Canada.

The facilities are among the

nicest we have seen in all Tanzania—well set up and

extremely clean with private showers, spacious bedrooms

and more than enough play areas. The majority of the

children suffer from albinism. Because of that they

aren't allowed to leave the compound without adult

accompaniment. Attacks on young children with albinism

are a constant threat. Extremely young children are the

target of witch doctors for their clients. Both boys and

girls love kicking the ball around, squealing with

delight at every imaginary goal. Some boys were

recovering from minor surgery and confined to the

infirmary. Matt enjoyed helping assemble some of their

gifts. Even after our short time with the kids, it was

not easy to leave. We walk out through the heavy iron

gate. The children cannot be allowed such freedom. They

are captives because of the unique color of their skin.

Too much evil intent lurks in the minds of so many

people in this land which still remembers the scars of

the slave trade.

The weather is heating up—no

rain for the past three days. We hope that this is not

the end of the rainy season. The corn is as high as the

Serengeti elephant’s eye, tassels reaching right up to

the cloudless blue sky. If the rains stop, the corn will

wither and die. Roads turn from muddy mires to mirages

of dust clouds with red dust blanketing everything—the

type of dust that covers you and then gets into your

bed, under the covers and into your nose, dehydrating

your whole system.

Farewell Tabora

Tabora was refreshing, with

daily rains drenching the region. However, here in Dar

es Salaam, the Casablanca fan churning above provides

feeble relief from the oppressive noon-time heat. (The

electricity cut out two hours ago, and I feel ready to

be flipped like Mama Tatu’s bubbling chapati). Waves of

humidity blanket Tanzania's largest city, located on the

coast of the Indian Ocean. I pause in my self-pity and

remember the inhuman two-to-three month slave march

through Tabora to this very area and then on to the

weekly market in Zanzibar.

Recalling our months in Tabora conjures a touch of

homesickness. We remember Mfaume guiding us to the right

bus at 5:30 a.m. through inky blackness and drizzling

rain. Hugging this wonderful man made the ache of

leaving more tangible. Somehow it just didn't seem

right. Hadn’t we just arrived yesterday? We sped through

the darkness blurring the familiar landmarks we knew so

well.

Our last view of the Malumba

project was through cascading torrents from inside the

car. The security wall and clinic foundations are

complete. Although the amount of work we were physically

able to complete seemed meagre, we were able to

encourage the crew. The local experts continue with

construction. Now they can envision their clinic

offering a better life and purpose for their families in

the often-forgotten Malumba district, a much more

manageable walk for those in the district.

One

haunting image returns of a young mother with her

handicapped four-year-old son strapped to her back. They

were on their daily, three-kilometre trek to work in her

rice field. He was born with a genetic defect and

although his muscles will never fully develop, he is

gaining weight. Her husband blamed her for her son's

defect and kicked her out of their home. She refuses to

remarry because she fears no one could value her child,

so she has given her life to care for her son. His life

expectancy is not long. Hardship is a part of everyday

life here in Tanzania. We watched her fade along the

red-earth path, their daily food supply balanced on her

head, hoe in hand and her helpless baby slung on her

back. This emphasized the urgency for the health project

in this area.

One

haunting image returns of a young mother with her

handicapped four-year-old son strapped to her back. They

were on their daily, three-kilometre trek to work in her

rice field. He was born with a genetic defect and

although his muscles will never fully develop, he is

gaining weight. Her husband blamed her for her son's

defect and kicked her out of their home. She refuses to

remarry because she fears no one could value her child,

so she has given her life to care for her son. His life

expectancy is not long. Hardship is a part of everyday

life here in Tanzania. We watched her fade along the

red-earth path, their daily food supply balanced on her

head, hoe in hand and her helpless baby slung on her

back. This emphasized the urgency for the health project

in this area.

We will miss Christopher, the

owner of the local soda shop. He had become our hot-day

friend. He kept his Coke and Pepsi varieties deliciously

cold in glass bottles and offered us seating on his

concrete front counter or in the VIP lounge out back on

wobbly plastic chairs under his laundry and the coconut

tree. We wondered if we would be there long enough to

experience a coconut fall from one hundred feet.

Although Matt was not a soda fanatic, the ritual and

friendship became as refreshing as the cheap pop.

Ironically, we will not miss the church services!

Beautiful African voices are amplified into distortion.

The ear-splitting volume is so foreign to us

mzungus

(white foreigners). On the

frequent occasions that the electricity cuts out, then

we actually enjoy the harmony. But all too soon the

generator is fired up and the monster speakers swallow

the beautiful voices. Often the preacher will be of

equal volume. This phenomenon causes us pain as we

slip each other ear plugs. Sister Magdalena has an

amazing resonant voice and we long to hear her, but alas

she is swallowed in distortion. The invasion of the mega

amps has become an issue here. We are donating our

earplugs to Hanneke for future guests.

The old Orion Railway Hotel

lives in an era when throngs of elegant passengers were

greeted in its lobby. They arrived from distant ports

and then traveled across the country to Tabora. The now

faded facade and drizzling fountain welcomed visitors to

the Tabora region for years. We took Baraka for “chips

mayday” (a French-fry omelette). He felt like a special

gentleman—although I am not sure that delicacy was on

the original menu in the Orion’s heyday. Most of the

sounds from the railway are now the shunting of cargo

cars, although the government has promised significant

spending on the rail infrastructure. So possibly

travellers may once again make the incredible journey in

comfort, crossing the Rift Valley through wildlife

reserves and past villages made alive by the vendors

selling fresh mangoes, honey and papayas. Maybe the

Orion may once again offer exotic local specialties.

Hanneke, Naomi (Hanneke’s house

helper of fifteen years), Mahona, Mfaume, Jackie, Kiri,

Baraka and Faraja were quieter as we left. Like the

early guests at the Orion, we leave feeling spoiled and

spiritually refreshed. A taste of heaven under the shade

of the mango trees close to the railway tracks and

always near the heart of God’s special people.

Uganda

Our single-engine Cessna sputtered to life.

Soon we are above the Ugandan expanse in our Mission Aviation Fellowship

flight out of suburban Entebbe. Red-brown arteries—dirt roads and

paths—intersect the green tapestry sprawls below. Villages remain hidden

from our altitude.

One and a half hours later we descend toward

a narrow mud strip. After touchdown we see Leah and several friends

sheltered from the heat. She is excited to see friends from Canada.

The Karimojong people are attempting

to put some distance from their violent past. Arguments over cows, land

or wives were resolved with smoking guns. The Ugandan government has

successfully reduced the gun obsession in most of the Karamoja region

and its people are beginning to feel safer. (Prisoners were sent to the

Karamoja area on work projects because the gun-toting men of this region

were so feared that the prisoners never attempted to escape.) They live

in spread outmostly in Bandas (mud huts with a thatched grass roof.

Small villages are often one extended family—a husband. his wives and

their children.

L eah's

home is her Banda, a round brick hut with a thatched roof as well as a

separate kitchen Banda. Leah enjoys her life here and does not feel any

real hardship.

eah's

home is her Banda, a round brick hut with a thatched roof as well as a

separate kitchen Banda. Leah enjoys her life here and does not feel any

real hardship.

Her day begins with Bible study and a briefing

at the clinic. An aged man, wrapped in a typical red and blue checkered

Masai tribal blanket, uses his stick to make his way over the

treacherous landscape each day. His sightless gaze is fixed straight

ahead, but there is an expression of joy on his face as he sits bolt

upright in the middle of the group.

We struggle to keep up with Leah and her two

health care workers, Naduk and Lomuria, on our forty-five minute trek to

Kopetatum. The village is surrounded by a lethal hedge of thorn bushes

to keep intruders out. (At night another thorny clump is pulled into the

opening from inside to complete the security barrier). The women gather

when we arrive. We are invited to sit on the only smooth area available

(packed cow dung and mud) with the others. We are introduced to Lucia, a

blind grandmother, who stretches out her weathered hand and we exchange

blessings. She smiles a toothy smile and announces that I am welcome and

that my Karimojong name would be “Lokut,” since I came to visit them on

a breezy day. (Matt receives the name “Loyep” for one who cuts small

branches). The health care workers teach their basic sanitation and

disease control lessons. Then they answer questions and offer advice on

conditions that need improvement. Greetings and goodbyes to the

Karimojong are long and sincere, but we finally leave. Knowing that we

will never pass this way again, we savour the smells, sounds and voices.

On to the next thorn bush-surrounded village.

We

joined Leah’s evangelist, Simeon Peter, on his long walk in the

scorching sun, with only a gentle breeze. Trails crisscross, leading in

many directions. We wade barefoot through a muddy stream. Finally we

spot a few men under a tree and greet them. Soon, other men and boys

appear, as if by magic. Simeon begins with singing. The Karimojong men

spend much of their lives, just debating and sitting under trees while

the women do the hard work. This pattern has changed little over the

ages. The outdoor Bible class with the men is stimulating and many

interact with keen interest.

We

joined Leah’s evangelist, Simeon Peter, on his long walk in the

scorching sun, with only a gentle breeze. Trails crisscross, leading in

many directions. We wade barefoot through a muddy stream. Finally we

spot a few men under a tree and greet them. Soon, other men and boys

appear, as if by magic. Simeon begins with singing. The Karimojong men

spend much of their lives, just debating and sitting under trees while

the women do the hard work. This pattern has changed little over the

ages. The outdoor Bible class with the men is stimulating and many

interact with keen interest.

Leah’s home base is close to the mountain

range—an ancient volcano. We went for a long walk—made longer by the

number of people we had to stop and greet along the way. The people love

Leah and appreciate that she has invested much of her life to be with

them.

Back in Leah’s Banda she shows us where the

Black Mamba snake slithered in for a visit one day. She talks about her

hopes of seeing health and education become more vital and more churches

planted. She only mentions the two-inch thorn that penetrated her sandal

last week—part of the territory she has chosen. This is Leah's home and

these are her people—young and old. When the Karimojong greet her by

name, they do so with a discernible tone of love and gratitude.

We

are suffering from our long gruelling flight on our journey into

Africa. Matt’s fiancée, Hayley, Mom and sister said goodbye at

Toronto Pearson. As we were jostled through security screening, I

left my laptop in my backpack for inspection. So I was ushered back

through the whole process. This time all went well. I quickly

grabbed my stuff and hustled on. Five minutes passed when I realized

I was about to lose my pants: “My belt,” I mused, "my wallet and

phone!" I returned a third time and everything was sitting in the

open, waiting for anyone to pick them up.

We

are suffering from our long gruelling flight on our journey into

Africa. Matt’s fiancée, Hayley, Mom and sister said goodbye at

Toronto Pearson. As we were jostled through security screening, I

left my laptop in my backpack for inspection. So I was ushered back

through the whole process. This time all went well. I quickly

grabbed my stuff and hustled on. Five minutes passed when I realized

I was about to lose my pants: “My belt,” I mused, "my wallet and

phone!" I returned a third time and everything was sitting in the

open, waiting for anyone to pick them up.

The

security wall at the new Malumba health, education and evangelism centre

will enclose 20 x 25 metres. The main building, in the western end of

the enclosure will be 5 x 10 metres with two rooms and a covered

verandah which will serve as a classroom and waiting area. Two bathrooms

will be built at the opposite end of the enclosure. Moringa trees will

be planted inside the walls. Moringa is recognized for its health

benefits: from the dried leaves to the seeds contained in longish bean

pods dangling from their branches.

The

security wall at the new Malumba health, education and evangelism centre

will enclose 20 x 25 metres. The main building, in the western end of

the enclosure will be 5 x 10 metres with two rooms and a covered

verandah which will serve as a classroom and waiting area. Two bathrooms

will be built at the opposite end of the enclosure. Moringa trees will

be planted inside the walls. Moringa is recognized for its health

benefits: from the dried leaves to the seeds contained in longish bean

pods dangling from their branches. A

Mediterranean blue sky with pristine white clouds and the sweltering sun

beat down on the plot of land. The trenches have been prepared. So let

the construction begin! Some sparse clouds offer fleeting relief.

A

Mediterranean blue sky with pristine white clouds and the sweltering sun

beat down on the plot of land. The trenches have been prepared. So let

the construction begin! Some sparse clouds offer fleeting relief.

eah's

home is her Banda, a round brick hut with a thatched roof as well as a

separate kitchen Banda. Leah enjoys her life here and does not feel any

real hardship.

eah's

home is her Banda, a round brick hut with a thatched roof as well as a

separate kitchen Banda. Leah enjoys her life here and does not feel any

real hardship.